Science has always played a major role in every period of human evolution. Back in 460 BC people performed primary occupations such as farming, fishing, cattle rearing etc. along with a few jobs involving technical and scientific knowledge to full fill the needs of the army. Their educational curriculum, at that point of time was all about natural sciences. While the world was learning to get a good yield in their fields, Greeks were studying philosophy, mathematics and astronomy. One of them was Democritus, a natural philosopher. He was taught about the five elements of nature – air, water, fire, earth and ether (matter that made up the sun and moon). He wasn’t convinced with this theory. He said that there are particles which are extremely small which make up the world. He named them atomos – indivisible. This was the beginning of particle physics.

Atomic Theories

According to Democritus, atoms were indestructible, solid but invisible and homogeneous. Sounded good but incomplete. With the development in scientific research and technology various ideas came up to explain the building blocks of nature.

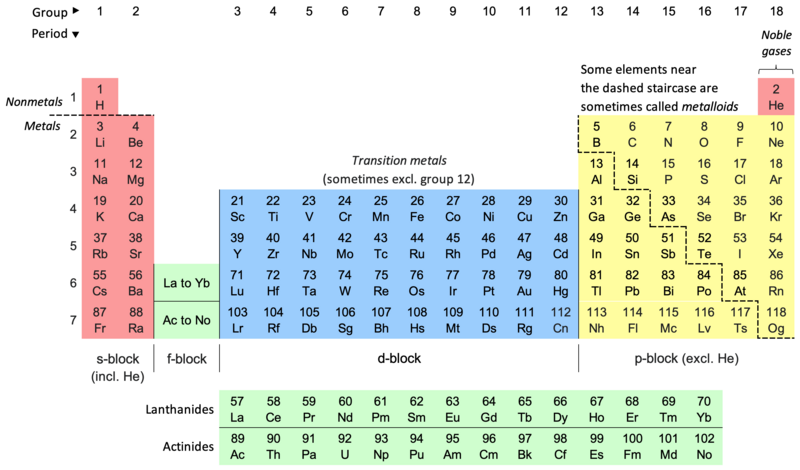

In the late 1800s scientists thought the universe was made up of just 80 elements which were placed systematically in the periodic table by Mendelev. Was each element made up of a different type of atom? Were there 80 different atoms?

In the late 1800s scientists thought the universe was made up of just 80 elements which were placed systematically in the periodic table by Mendelev. Was each element made up of a different type of atom? Were there 80 different atoms?

J.J. Thomson was the first to propose a coherent atomic theory. He is also credited with conceptualizing an apparatus resembling a modern-day particle accelerator. By varying the voltage across plates and measuring the deflection of beams, Thomson calculated the mass of particles. He discovered that these particles were 2000 times lighter than hydrogen atoms, the lightest known particle at the time. This unknown particle was the electron, the first fundamental particle identified. Remarkably, even a century later, electrons remain one of the best-measured particles. Thomson’s findings led to the first atomic model, known as the “Raisin Pudding” model, where the atom was envisioned as a positively charged “pudding” with embedded negatively charged electrons.

Next came Ernest Rutherford, who utilized beams of radioactive decay. His work area still bears traces of radioactivity, even a century after his experiments. Rutherford directed a beam of particles at a thin gold foil. Most particles passed through, some deflected at small angles, but a few (precisely 1 in 8000 alpha particles) bounced back. It took Rutherford two years to realize that the atom has a nucleus at its center, which is extremely small but accounts for 99% of the atom’s mass. The remainder is mostly empty space. This led to a new atomic model, akin to our solar system, with a central nucleus and orbiting electrons. Rutherford and James Chadwick later discovered that the nucleus comprised positively charged protons and neutrally charged neutrons.

Modern-day particle physics

With the development of quantum mechanics, we now understand that while the nucleus resides at the center of an atom, the precise positions of electrons within their respective distinct shells cannot be predicted. Electrons exist in probabilistic clouds rather than fixed orbits.

Around the 1900s, scientists discovered unknown particles bombarding the Earth, originating from cosmic rays. Determining the exact time and location of these cosmic ray particles was challenging. To study them, scientists developed their own particle accelerators. In just a few decades, this led to the discovery of about 80 new fundamental particles, reminiscent of the chaotic period during Mendeleev’s time.

Amidst this chaos, Murray Gell-Mann identified patterns explained through symmetries. He proposed that the entire array of approximately 80 fundamental particles was composed of three basic particles, which he called quarks (up & down in this context). This groundbreaking realization brought a new level of order and understanding to the field of particle physics, highlighting the elegant simplicity underlying the apparent complexity of the subatomic world.

Forces, the agents of change, are crucial for understanding the standard model of particles. Gravity, the force that made an apple fall, was the first to be discovered. However, it is relatively weak and thus does not occupy a place in this model. This is because gravity is theorized to be mediated by a particle known as a graviton, which has yet to be discovered. Importantly, ignoring gravity at quantum scales does not affect experimental outcomes.

The force that holds soap bubbles together and allows a flame to burn is the same force that enables us to push and pull objects, powers electronic devices, and gives us a view of the beautiful universe—the electromagnetic force. This force holds atoms in place within objects and keeps electrons in place within atoms. It also causes electrons to repel each other. Thus, when you hold a ball in your hand, gravity pulls it down, but the electrons in your hand repel the electrons in the ball, preventing it from falling through your hand. The photon is the particle responsible for the electromagnetic force. There’s much to discuss about its wave-particle duality, the photoelectric effect, quantum electrodynamics, and more.

Protons, which are positively charged, exist within the same nucleus. According to electromagnetism, they should repel each other and cause the nucleus to blow apart, yet they remain stable due to another force: the strong nuclear force. This force keeps the nucleus intact. Despite understanding the effects of the strong nuclear force, certain phenomena remained unexplained, necessitating the discovery of another force—the weak force. The gluon mediates the strong force, while the W and Z bosons represent the weak force. Interestingly, scientists observed that electrons are emitted from the nucleus during beta decay, a process explained by the weak force.

These forces—electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear—form the foundation of the standard model of particle physics, explaining the interactions and behaviors of fundamental particles.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Positrons are electrons with positive charge which are emitted from the nucleus during ß decay. Rico Fermi later explained that there was a weak force which could convert proton into neutron or neutron into proton and emit electrons, positrons or neutrinos from the nucleus !! With this, we can now understand the working of the atoms.

So is this the end? No ⊙﹏⊙

The Electroweak Force – combination of the weak force and electromagnetism (which is already a combination of electricity and magnetism) !!

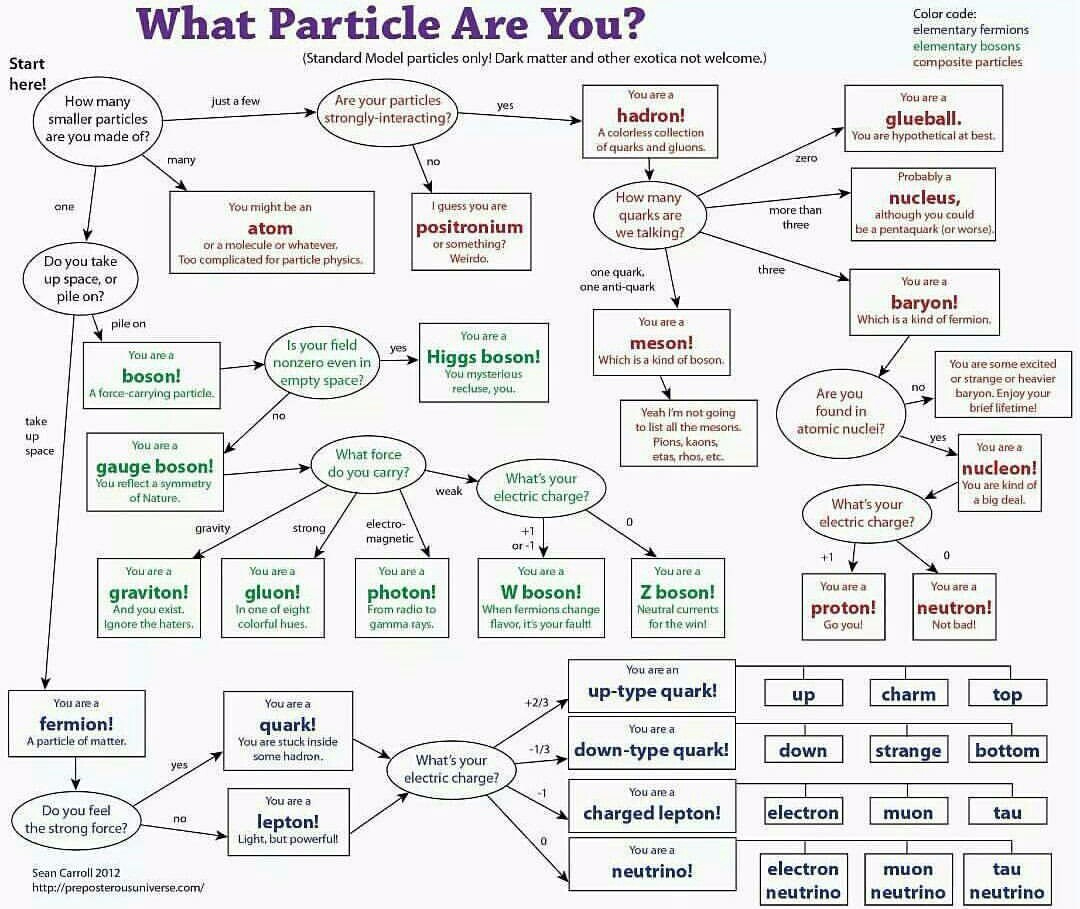

This is the end of the post but there are more particles to come and blow your mind. What particle would you want to be? I’m definitely Higgs Boson–the god particle :p

Images Used

1. “Periodic Table of Elements“; Credit: Sandbh

2. “Standard Model of Elementary Particles“; Credit: Cush

3. “What Particle are you?“; Credit: Sean Carroll